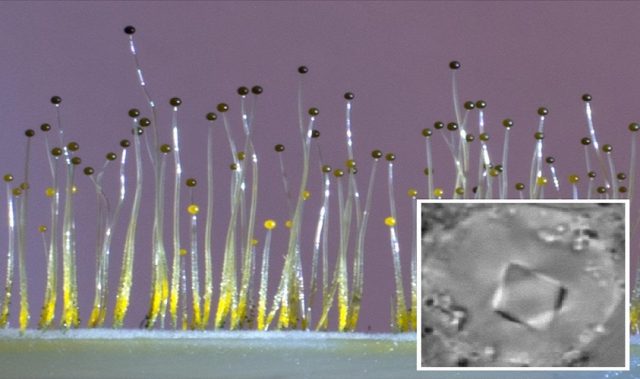

AsianScientist (Jan. 26, 2016) – Walk into any microbiology lab, and you will likely be greeted by towering stacks of agar plates, each one home to a menagerie of microorganisms. Agar, a jelly-like substance derived from seaweed species of the genus Gelidium, is perhaps microbiology’s most important laboratory reagent, long used as a solid substrate to culture and isolate bacteria.

Now follow your nose into a home kitchen in Asia, and chances are that you will find agar there as well. Apparently invented by happy accident in 17th century Japan when a forgetful innkeeper left seaweed extract out in the cold, it has been used for centuries as a thickener, and to make all manner of deliciously wobbly desserts.

In December, Nature News reported that agar supplies have been affected by a global shortage of Gelidium seaweed. Because it grows on rocky seabeds and requires turbulent water for a steady supply of nutrients and oxygen, Gelidium cannot be farmed.

Instead, it’s harvested by divers, or collected when washed ashore by the tide. But dwindling seaweed populations and overharvesting have led Morocco, currently the world’s largest Gelidium supplier, to restrict annual harvests and place quotas on foreign exports.

As a result, wholesale agar prices have nearly tripled to US$35-45 per kilogram—an all-time high. Thermo Fisher Scientific and Millipore Sigma, two major suppliers of laboratory reagents, have already stopped selling some agar products.

If the situation worsens, it’s likely that many microbiology labs will have to scale back on experiments. And they might not be the only ones affected. Agarose, a component of agar, is used to make gels for the separation of DNA and protein molecules—a basic technique for practically every lab.

From Malaysia to Japan and Germany

As it turns out, agar’s journey from humble kitchen ingredient to indispensable laboratory reagent is a fascinating story, one that spans centuries and continents.

Despite its Japanese origin, agar takes its name from the Malay word for Gelidium, agar-agar. It’s possible that this came about because the Dutch, who had treaty ports in Japan in the 19th century, brought the concept from there to their colonies in Indonesia.

We now move halfway around the world to the Berlin laboratory of Robert Koch, who today is considered one of the pioneers of modern microbiology. In the late 19th century, germ theory—the concept of disease being caused by microorganisms—was not yet widely accepted. To provide evidence for this theory, Koch’s lab was developing methods to grow bacteria on solid surfaces, where they would form discrete spots or colonies—each an individual species which could then be isolated and grown in pure culture.

From trying to coax bacteria to grow on slices of potato, they moved on to using a jelly made from nutrient broth and gelatin, spread out in Petri dishes (one of the perks of having their eponymous inventor, Julius Petri, as a lab member). But this didn’t work out too well, either—the bacteria were able to digest gelatin, and it also softened too much at the preferred incubation temperature of 37 degrees Celsius, leaving behind a soggy semi-solid mess.

Enter Angelina Hesse, wife of Walther Hesse, another of Koch’s lab members. She had the dubious honor of cooking for her family as well as for the bacteria—the beef stock used in their nutrient broth came out of her kitchen. Fortuitously, the Hesses had Dutch friends who had lived in Indonesia. From them Angelina learned about agar—and suggested to Walther that he use that instead of gelatin to grow his bacteria.

Her insight resolved a number of technical issues the lab was facing. While gelatin is derived from animal collagen, agar is a polysaccharide, or sugar polymer, which most bacteria cannot digest. It also has a higher melting point than gelatin, and stayed solid at temperatures optimal for bacterial growth.

Aided by such culture methods, Koch and his lab would go on to isolate the bacteria that cause tuberculosis and cholera. His work helped to establish the germ theory of disease, and paved the way for the development of microbiology as a discipline. Agar, of course, came along for the ride—thanks to a confluence of colonialism, global trade, and a resourceful home cook.

Fast forward to our (seaweed-scarce) present day. It’s unclear if Morocco’s export restrictions on seaweed will help conservation efforts, and the European Commission has complained, to little effect, that they violate free trade agreements. Meanwhile, there are still no real alternatives to agar for growing microbes—unless you feel like slicing potatoes.

This article is from a monthly column called The Bug Report. Click here to see the other articles in this series.

———

Copyright: Asian Scientist Magazine; Photo: Nathan Reading/Flickr/CC.

Disclaimer: This article does not necessarily reflect the views of AsianScientist or its staff.