AsianScientist (Dec. 30, 2015) – Singapore, an island city-state just north of the equator, has a hot and humid climate. To compensate, Singapore’s buildings maintain some of the world’s coldest indoor temperatures, powered by air-conditioners that whir along day and night, 24/7.

The late Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore’s first prime minister, used to joke that when indoors he needed to wear clothes intended for European climates. More seriously, Mr Lee has argued that the greatest invention of the 20th century is the air-conditioner, especially for those living in the tropics.

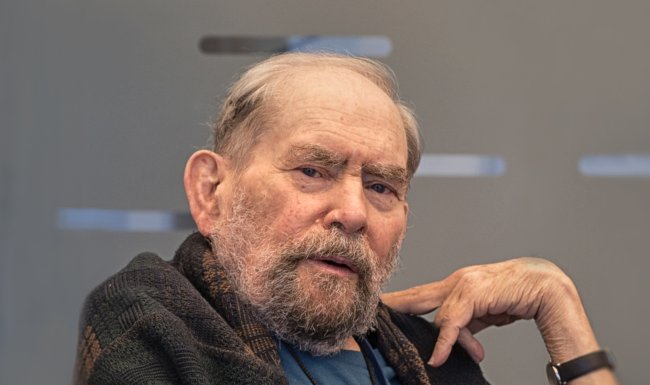

But in order to run air-conditioners efficiently, intelligent thermostats are needed. This is where Hang Chang Chieh, professor of electrical engineering at the National University of Singapore (NUS), comes in.

“When it rains, the air-conditioner continues to work, wasting a lot of energy. It is not only energy-inefficient, it also makes people very uncomfortable,” says Professor Hang.

To improve the technologies behind air-conditioners—and many other consumer goods—Professor Hang has, among other things, taken sophisticated control systems found in the military and aerospace industries and made them cheaper and simpler.

“Intelligent” control systems

As a student Professor Hang built his own radio and hi-fi audio speakers, and had a knack for repairing things. His PhD research topic covered adaptive control, a field where control systems are programmed to detect changes in the environment and adjust their parameters automatically.

This field is at the heart of the aerospace industry, where adaptive control systems are critical in stabilising airborne aircraft. For example, as a plane progressively depletes its fuel supply along its flight path, lightening its load, it needs to detect the change of its mass to maintain a comfortable experience for those on board, while burning less and less fuel to maintain its speed. Conversely, as and when air resistance increases, the plane needs to burn more fuel.

But the technology used in commercial airplanes—and also in space programmes and the military—remains too expensive for everyday applications such as air-conditioner thermostats. To sharply reduce costs, Professor Hang had to imbue these control systems with some kind of artificial intelligence.

These systems are “intelligent” in that they are able to measure a variable (e.g. the outdoor temperature after a rainy spell) and adjust the control parameters accordingly (e.g. raise the temperature setting on an air-conditioner thermostat) without the need for human intervention.

Beyond air-conditioners, intelligent control systems have much wider application in robotics, disk drive manufacturing and even in healthcare.

“We are now coming up with the next generation of rehabilitation equipment, which are light weight, low cost, and can be rented or borrowed and put at home, cutting out travelling time,” says Professor Hang.

A clarion call to serve

Like many young people growing up in Singapore today, CC—as he is often referred to—was determined to get into medical school.

In the 1960s, medicine was offered only by the University of Singapore—not by the country’s only other university, the Chinese-language Nanyang University.

Professor Hang, who was then enrolled at the Chinese-language Chung Cheng High School, realised that he would not be able to pass the medical school qualifying exams if he was not proficient in English. In 1964, he transferred to Anglican High School, also a Chinese-language school but allowed him to take his papers in English and was strong in biological subjects.

One incident, however, would change the course of his life. During his school holidays after his first year studying for a higher-level certificate (HSC, the precursor to the GCE ‘A’ levels), he read in a magazine that Japanese youth were applying in droves to study engineering as they wanted to help rebuild the country’s shattered economy after the Second World War.

Intrigued, Professor Hang started reading lots of engineering articles and introductory textbooks. It was a revelation to the wannabe-doctor, who changed his mind and decided to become an engineer instead.

“Singapore was in bad shape in the 60’s; we were still a colony. There was poverty and many people could not afford medical healthcare,” he says. “I thought, at that time, instead of being a doctor, if I became an engineer, I could help the country create wealth, and more people could afford healthcare.”

It was all rather anti-climactic when Professor Hang found out that the University of Singapore did not have an engineering programme in 1966. Undeterred, he studied in the electrical engineering degree course at the Singapore Polytechnic (the only polytechnic in Singapore at that time) for two years before the University of Singapore department of engineering absorbed the programme. His entire graduating class had only 40 engineering students, of whom 18, including him, majored in electrical engineering.

Professor Hang later received a bond-free scholarship from the UK government to pursue a PhD at the University of Warwick.

His post-PhD career as a control system designer at the Shell Eastern Petroleum Company ended after three years when he received a phone call from Jimmy Chen, head of NUS’s department of electrical engineering, who wanted to recruit him. Acquiescing, Professor Hang took an immediate pay cut of 20 percent, a choice he has never regretted.

The first of many five-year plans

Though the veteran engineer has long been focussed on his research into control systems, he has also had to wear many other hats along the way.

NUS appointed Professor Hang consecutively to three senior roles—vice-dean of the faculty of engineering in 1985, head of the department of electrical engineering in 1990, and deputy vice-chancellor (research and enterprise) in 1994—during which time he has had to oversee the university’s transformation from a primarily teaching institution to one that is research intensive.

Part of his mandate was to raise research funds. “I was one of the most expensive beggars around. I asked for hundreds of thousands, millions,” he says with a laugh.

In parallel, he became the founding deputy chairman of the National Science and Technology Board (NSTB) in 1991, a part-time position he held until 1999. The government gave NSTB just five years to produce concrete results, such as helping to attract foreign investment and growing local industries.

“We had to make sure the first five years succeeded so that we would have a next five-year plan,” he says.

By seeding a group of talented researchers, his efforts would eventually bear fruit and lead to multinational companies making significant investments here. The first five-year National Technology Plan in 1991—with a budget of S$2bn (S$3.1bn in today’s dollars)—was renewed; two decades later, the 2011 plan had a five-year budget of S$16.1bn.

For his contributions to championing research in NUS and NSTB, Singapore awarded Professor Hang the Public Administration Medal (Gold) in 1998, and the National Science and Technology Medal in 2000. In 2001, NSTB was renamed the Agency of Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR), where he was seconded full-time from 2001 to 2003 as its executive deputy chairman.

Wealthy in knowledge

Professor Hang remains active in engineering education—as head of NUS’s division of engineering and technology management since 2007 and as executive director of NUS’s Institute for Engineering Leadership since 2011.

He encourages bright, young people to study engineering because of the many academic, industry and entrepreneurial careers available to them. To prepare them for a life of entrepreneurship, the NUS faculty of engineering is making curricular changes to allow students to enter a design and innovation pathway.

The engineer in him also wants to let the facts speak for themselves. He cites a 2013 Wall Street Journal article, which described how participants of an investor conference voted engineering as the number one subject to study for a life of innovation, and their top choice for their children’s college major. A 2015 article in The Telegraph also noted that more than a fifth of the world’s wealthiest people studied engineering in university.

“Parents of course always say those in the finance sector, property, can make money,” he says.

But regardless of one’s career ambitions, he believes engineering will provide a strong foundation. Consider his daughter, 33, who studied electrical engineering and later worked in public service, consulting and then banking.

Nevertheless, despite the allure of these high-paying professions, Professor Hang has some financial advice for Singaporean youth, including his daughter and son, 26.

“Don’t chase money, let money chase you. When you are successful in your work, at the minimum, you will be wealthy in knowledge.”

Singapore should certainly be thankful that Professor Hang himself chose not to “chase money”. Among his many engineering and research contributions to the country, one bears reiteration: the “intelligent” air-conditioner, which will help reduce energy use—and sweater sales—in this tropical island.

This feature is part of a series of 25 profiles, first published as Singapore’s Scientific Pioneers. Click here to read the rest of the articles in this series.

———

Copyright: Asian Scientist Magazine; Photo: Bryan van der Beek.

Disclaimer: This article does not necessarily reflect the views of AsianScientist or its staff.