AsianScientist (Jan. 6, 2015) – By Nalaka Gunawardene – Managing disaster early warnings is both a science and an art. When done well, it literally saves lives—but only if the word quickly reaches all those at risk, and they know how to react.

We have come a long way since the devastating Asian Tsunami of December 2004, which caught Indian Ocean countries by surprise. Many of the over 230,000 people killed that day could have been saved by timely coastal evacuations.

The tenth anniversary of that mega-disaster, being marked this month, is a good time to take stock of what has been accomplished since.

The good news is that advances in science and communications technology, greater international cooperation, and revamped national systems have vastly improved tsunami early warnings during the past decade. However, some critical gaps and challenges remain.

Tight windows

Early warnings work best when adequate technological capability is combined with streamlined decision-making, multiple dissemination systems and well-prepared communities.

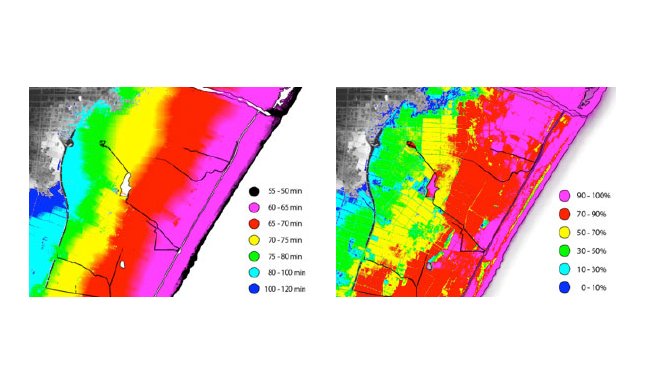

Rapid onset disasters—such as tsunamis and flash floods—allow only a tight window from detection to impact, typically 15 to 90 minutes. Other hazards, such as cyclones and floods, may occur within a few hours or days of detection.

When governments act quickly and resolutely, benefits are enormous. Simple preventive actions, such as mass evacuations, can save countless lives, says Brahma Chellaney, a professor of strategic studies at the Centre for Policy Research in New Delhi.

He cites the example of evacuating over half a million people from the southeastern Indian coast in October 2014 ahead of the strong tropical cyclone Hudhud—one of the fiercest to hit the region in years. That kept the death toll to fewer than 50, whereas a cyclone in the same area in 1999 killed 10,000.

When it comes to tsunamis, it is a real race against time. Effective tsunami warnings require very rapid evaluation of undersea earthquakes and resulting sea level changes, followed by equally rapid dissemination of that assessment.

In 2004, the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center (PTWC) in Hawaii, needed an average 18 minutes to process monitoring data and issue a warning. By 2014, this has been reduced to seven minutes according to Stuart Weinstein, PTWC’s deputy director.

Following the 2004 disaster, the Indian Ocean Tsunami Warning and Mitigation System (IOTWS) was set up in 2005 under UNESCO’s Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission. It is a regional collaboration that brings together three regional tsunami service providers—scientific facilities operated by the governments of Australia, India and Indonesia—and over a dozen national tsunami centers. The latter are state agencies designated by governments to handle in-country warnings and other mitigation activities.

Based on regional level tsunami threat assessments, each government must decide if and when to issue national or local warnings. With lives and livelihoods at stake, there is much pressure to get it right. But one cannot be timely and totally accurate at the same time.

As Rohan Samarajiva, chair of LIRNEasia, an information and communication technologies policy and regulation think tank, and I noted last year, “Only governments can balance these factors. No other entity can take on the responsibilities and attendant liabilities of issuing public warnings that may result in mass evacuations.”

Timely decisions taken on the basis of the best available evidence require clear protocols within government. But often, turf wars and the lack of a clear demarcation of authority between different actors lead to slow decision-making.

ICT proliferation

Even the most advanced early warning systems are only as good as their ability disseminate warnings efficiently and through multiple pathways. The proliferation of information and communication technologies (ICTs) enhances outreach—but it can sometimes complicate matters.

Having more information sources, channels and access devices is certainly better than none. However, the resulting cacophony makes it harder to achieve a coherent and coordinated response. In the social media age, governments no longer have a monopoly over public information.

That was evident on 11 April 2012, when an 8.6-magnitude quake occurred beneath the ocean floor southwest of Banda Aceh, Indonesia. Several countries issued quick warnings and some also ordered coastal evacuations. For example, Thai authorities shut down the Phuket International Airport, while Chennai port in southern India was closed for a few hours.

In the end, the quake did not generate a tsunami (not all such quakes do), but it triggered considerable chaos. In Sri Lanka, coastal bus and train services were stopped, electricity was shut down and public offices were abruptly closed. The Department of Meteorology, designated as national tsunami warning body, used live phone interviews on radio and TV instead of its own website or social media.

A few journalists and activists kept tweeting ground-level updates and news from international wire services. Unless governments communicate in a timely and authoritative manner during crises, that vacuum will be filled by multiple voices. Some of these may be speculative, or mischievously false, causing confusion and panic.

Nurturing trust

Thus, early warning systems need to be anchored in public trust and credibility. As I noted after the April 2012 events, “Disaster early warnings are pure public goods…Public trust is the lubricant that will move the wheels of law and order as well as public safety in the right direction.”

Another challenge for early warning systems is to guard against the ‘cry-wolf syndrome’. As rapid decisions are made using imperfect information, errors of judgement can—and do—happen.

For example, three out of every four tsunami related coastal evacuations in Hawaii have later proved unnecessary. But PTWC has never missed any tsunami that did turn up since it was set up in 1949.

Too many false alarms and evacuation orders can lead to indifference, as reportedly happened in southern Bangladesh in November 2007. As tropical Cyclone Sidr approached, many communities ignored warnings, and more than 1,000 people died needlessly. A false tsunami alert and evacuation two months earlier had eroded their trust in the country’s well-established early warning system.

High-tech assessment and delivery systems would work best when national and local institutions are functional and communities are empowered.

These are key elements of disaster risk reduction, or DRR, now receiving greater attention as the frequency and intensity of disasters increase.

The Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP), the UN’s regional arm, says critical gaps remain in early warning and additional investments are required particularly at the local level.

Shamika Sirimanne, UNESCAP’s Director of Information and Communications Technology and Disaster Risk Reduction, says: “Reaching the most vulnerable people and remote communities at the ‘last mile’ with timely warnings is critical. An efficient end-to-end system is yet to be realized.”

An investigative report by Bloomberg this month also highlights the gaps. It found that while Sri Lanka and Thailand are better prepared to alert their people about oncoming tsunamis, it was less clear how the ‘last mile’ is going to be covered in India and Indonesia.

Writing one year after the 2004 tsunami, I called it the ‘long last mile’. Experiences of the past decade show just how hard it is not to falter on that final lap.

Science writer Nalaka Gunawardene has covered disasters for over 20 years as a journalist, and co-edited ‘Communicating Disasters: An Asia Pacific Resource Book’ in 2007. He is also a trustee of SciDev.Net. The views in this column are his own.

——-

Source: SciDev.Net.

Disclaimer: This article does not necessarily reflect the views of AsianScientist or its staff.