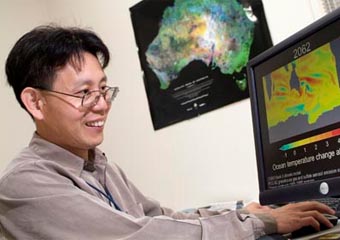

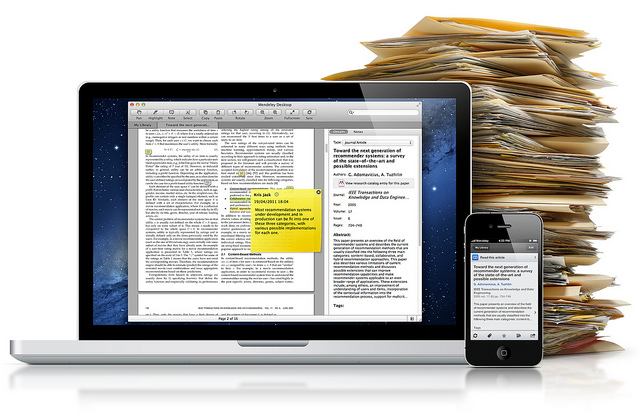

AsianScientist (Sep. 10, 2014) – As a Ph.D. student, Jan Reichelt found himself frustrated with the lack of social tools for researchers. This led him to co-found Mendeley, a free reference-management platform that enables researchers to organize and collaborate on their projects with greater ease and transparency. Mendeley is a cloud-based service available as a desktop program, a web service and an iOS mobile app (an Android app is in the works).

In April 2013, Mendeley was acquired by Elsevier, the Amsterdam-based scientific, technical and medical publisher. This spurred a controversy in the online research community with many concerned that the acquisition would be detrimental to the company’s open access model, or worried at how their user data might be exploited to further the corporate machinery of Elsevier.

Mr. Reichelt, who continues to lead Mendeley as its president, was in Singapore earlier this month visiting Elsevier offices. He talks to Asian Scientist Magazine about the strong need for innovative research-enabling tools, the impact of the merger with Elsevier and his thoughts on the company’s future.

Could you share with us the origins of Mendeley?

We started out as academics ourselves. As Ph.D. students we discovered the pain of organizing papers and documents, writing your own paper and creating your own citations. Collaborating with other researchers on an academic work—say a joint literature review—was also painful.

We wondered, “why isn’t there a cool social tool for academics?” There are so many, such as photo sharing and music streaming services, in other industries. Academia should arguably should be one of the most innovative industries, but there weren’t any great tools like those. Old-fashioned reference management software existed, but nothing that would allow people to have that great user experience seen in other industries.

Both my co-founders and I have always been very entrepreneurial, so we thought, “let’s do it ourselves.” We wrote up some specs, hired some engineers and developed a prototype. We used this to pitch investors in Europe for seed funding, and it just grew from there.

What are the demographics of Mendeley users?

We started out with Ph.D. students and post-docs, who are more likely to look up these types of tools, and go the extra mile to learn and adopt it. That is our largest userbase.

However, in the last one to two years, we’ve seen quite a few senior scientists—professors at MIT, Stanford—pick Mendeley up, and become heavy users. These guys are building their careers entirely on their research work, so they invest quite heavily into using a tool like Mendeley.

How do the functional aspects of Mendeley relate to the social network component? On the face of it, it seems difficult to reconcile research paper management tool with social network tool.

I would argue that research in itself is inherently social. Whether you’re part of a research group or lab or department—whether you’re in sciences, social sciences, or engineering—research is usually very collaborative. This concept spans across countries and institutions.

By anonymizing individual data, and exposing group data on a global scale, we can bring together information that’s dispersed across individual libraries, and enable new connections.

What interesting trends have you observed in the usage data that Mendeley has collected?

We found that there are a number of countries in Asia embracing Mendeley rapidly. Japan, which has a huge research density, Australia—but also countries like Malaysia and Indonesia, where we have one of our largest advisor pools.

This might be because other tools in the market with comparable features—except maybe on the social front—have upfront costs or require institutional licenses. With Mendeley, however, you can just go to the website and start using it. This comes from us being researchers ourselves, and saying: “why can’t we make a tool that is available to everybody?”

Social media is obviously a buzzword now, and perhaps a factor that has allowed Mendeley to flourish. What would you say are other factors?

The most important thing is that we are addressing a serious problem faced by a large number of people.

Our community-driven approach also helps. We have a global advisor program where we have 2,000 Mendeley advisors around the world who (for free) spread the word about Mendeley in their institutions, and at the same time provide us with feedback from the ground.

We have always stayed very close to the community and I think that has brought us a lot of credibility. People have been able to see that we implement the feedback provided.

For example: in Mendeley we have a flag feature that marks documents as as read or not read by individual users. Complaints came in that this flag would be eliminated too quickly if you clicked on the reference, even before actually reading the paper. Now, it only turns to “read” once you’ve actually opened the PDF file, and not just clicked on the reference. It’s a small thing, but one that can be a hassle to users, especially if those who have to churn through a few documents a day.

How has your acquisition by Elsevier changed—if at all—Mendeley’s philosophy of open access?

When we got together with Elsevier, the most important thing we agreed upon was the strategy: to build useful products for researchers and to get more value for the users out of these products. Whether by integrating ScienceDirect with Mendeley; by showing Mendeley readership on Scopus, which is already a publisher-neutral abstract-indexing database; or by allowing users to create Mendeley profiles automatically after submitting a paper to Elsevier.

I think we’ve also stayed true to our ethos of open science. We haven’t said we’re only on the side of open access; we’ve had to be realistic in wanting to build a tool that would work in the research ecosystem. And the research ecosystem consists of commercial, subscription-based content, as well as open access content. Mendeley can be used either way.

I do think we’ve contributed quite a lot to the open science mantra; for example via our open API. Here, people can access the data that the community has contributed without charge; applications can then be built on top of that data.

In fact, we just released the new version of the API developer portal a few weeks ago. Elsevier is more than happy to support us in this, because they believe it is the right thing to do.

What can we look forward to in the near-future from the intersection between Mendeley and Elsevier?

A similar experience to Google, where they use email, web search, YouTube data to personalize the user’s experience and make it more pleasant and efficient.

Eventually, you’d sign up to Mendeley with your name, and we’d know who you are. We’d pull your publication history from Scopus, using that to build your co-author network. We could then tell you automatically, “this is your network, here’s how you follow them”, and you’d be set up within the minute.

How do you address users’ privacy concerns in the midst of such integration?

We will not disclose to anyone what exactly you are reading; we will not make your personal library public, unless you yourself choose to do so.

But what we could do is cross-reference the documents in your library to the three million other Mendeley users. From there, we could tell you who you should be talking to, or what other content you might be of interest to you, based on other users’ behaviors.

It doesn’t mean we have to disclose what other people are reading; we can anonymize that & aggregate the data. This is something we’ve always been open and transparent about, and that has worked well.

Users can make public everything they do on Mendeley, but they don’t have to. We can’t force everyone to be open scientists, but we can build a tool that caters for all requirements of different user bases.

How do you see the evolving R&D/tech landscape continuing to shape Mendeley’s development?

One evolving area in the academic landscape that we are trying to understand and embrace is research data management. More and more publications require the researcher to also submit research data alongside the publication. So now we have a new problem field emerging for researchers: where do I store my data, publish it and so on.

We’re looking at how we can expand Mendeley to tackle this problem, because there’s no conceptual reason why you can’t also manage research data alongside your publications.

This is something that we couldn’t have done alone. But now with Elsevier, we have the resources, knowledge and funding to do so.

Mendeley started out as a primarily user-oriented tool. Will this continue to be the case?

Yes. We have agreed internally that our most important strategic objective is fulfilling user needs. This has been our history. There is no reason why this would change, as I believe this is what has made Mendeley successful.

Find out more about Mendeley here.

——-

Copyright: Asian Scientist Magazine. Images and supporting information: Mendeley.

Disclaimer: This article does not necessarily reflect the views of AsianScientist or its staff.