AsianScientist (Sep. 5, 2014) – The last six months of work at Asian Scientist Magazine have just flown by. In that time, I’ve read scientific papers from fields I’d never even heard of before, spoken to really interesting researchers and business people, and gained a much broader perspective on the practice and public impact of science.

Although it is perhaps still too early to say conclusively, to me, one of the main challenges of science journalism is walking the fine line between the popular and the significant. As a journalist, I try to balance between giving readers what (I think) they want, and my own opinion of what is important.

But wait, isn’t science supposed to be objective and neutral? That’s why journal articles are all written in passive voice right? Well for one thing, just imagine that there was no subjective content curation. What that leaves you with is an RSS feed of the many thousands of papers published every day, a veritable deluge of information without any context to make sense of it all. (And as for passive voice, don’t get me started, that’s perhaps an issue for another day.)

Science journalists are not gatekeepers in the sense that academic journals are. Given that we cover every field of science, it’s not possible for us to be able to critique the technical details of each paper published, a task that is still left to reviewers. But as a trained scientist, I am able to evaluate whether the study makes sense, whether the claims are overblown, and most importantly, how to fact check.

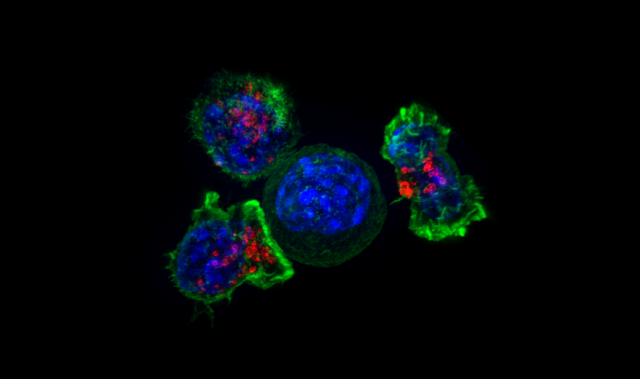

Just as how although I did my PhD on Toll-like receptor signaling, I’m able to understand and evaluate a paper on a systems biology approach to studying the immune system; there are skills related to understanding scientific information that can be transferred across disciplines.

Still, scientists generally don’t trust journalists to accurately report their findings. It is true that detail and nuance gets lost in a news article of 500 words based on a journal article of 5,000 or more words, of course. And sensationalism is a serious problem that can give the public the wrong impression.

However, the solution to poor communication is not no communication—insisting that everyone read the original paper or nothing at all—but better communication. We believe that scientific studies can be explained in an accessible and engaging way without compromising on the accuracy. It’s not easy, my personal experience is that it takes great perseverance to work through scientific articles outside your own discipline; but it can be done.

That said, it’s a very exciting time to be in science journalism. Science now has an unprecedented status in pop culture, with mad scientists replaced by adorable ones à la Big Bang Theory. (Which has even inspired a bizzare Chinese spinoff). More importantly, there is a great need for the general public to have a better grasp of scientific issues as we make collective decisions on hot button topics such as climate change, feeding the world population and what to do with personal genetic information.

As economic pressures force traditional media to close their science desks, and social media increases the speed of reporting demanded, science communication must evolve. Media outlets, from the social media-heavy IFLScience to the more than 100 year old institutions like Scientific American, are trying out new approaches and business models.

Here at Asian Scientist Magazine, we endeavor to bring you the most interesting science stories from Asia as we walk between the two worlds of science and journalism. Thanks for reading and following us as we find our voice.

This article is from a monthly column called From The Editor’s Desk(top). Click here to see the other articles in this series.

——

Copyright: Asian Scientist Magazine.

Disclaimer: This article does not necessarily reflect the views of AsianScientist or its staff.