AsianScientist (Jan. 3, 2017) – You may or may not have noticed it, but artificial intelligence (AI) is already a part of your everyday life. Every time you hail a ride on Uber, ‘discover’ a new band that you like on Spotify, or ask Cortana or Siri for directions, you are making use of AI that quietly hums away behind the scenes. AI is now such a hot topic that AI-focused companies managed to raise over US$1.5 billion in equity funding in the first six months of 2016.

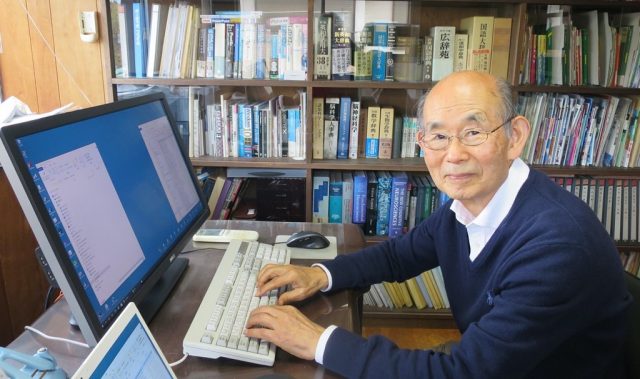

As excited as he is about these recent developments, industry veteran Dr. Hon Hsiao-Wuen is also somewhat surprised. Hon, who has taken on various roles at Microsoft over 22 years, remembers the dark days of the so-called ‘AI winter’ all too well. First captivated by the breadth and depth of AI as a college student in the early 1980s, he subsequently witnessed how the hype surrounding AI eventually failed to materialize, leading to discontinued funding and research in the 1990s.

This time, however, things are decidedly different, Hon told Asian Scientist Magazine. The corporate vice president at Microsoft, chairman of Microsoft’s Asia-Pacific R&D Group, and managing director of Microsoft Research Asia is confident that AI will transform every sector of industry, and even challenge our understanding of ourselves.

How close are we to simulating human intelligence with AI?

Hon Hsiao-Wuen: AI has really come a long way since the early days in the 1960s, when people were building what we call expert systems. These expert systems use databases of specialist knowledge to help make decisions, and can, for example, function like a doctor in making a medical diagnosis. Although AI started with expert systems, it soon reached limitations in terms of how many such expert systems could be built and the degree of expertise achieved.

The latest advances in AI have been made because of all the supporting infrastructure—from silicon chips and hardware to software, algorithms and, last but not least, the data. Today, if you can get the data you can build all kinds of expert systems. In many cases, these expert systems are already better than human experts, as seen in AlphaGo’s defeat of the human Go champion, Lee Sedol.

At the same time, at the philosophical level, I would say that AI has not defeated human intelligence. Humans can be human because we have so-called general intelligence; we know a bit of everything and some things we can create. Right now, scientists are working very hard on solving this problem of artificial general intelligence, trying to build a system that can not only recognize objects but can at the same time listen, learn and create. However, I think it will be a long time before AI can catch up.

Why is developing AI an important goal?

HHW: There are two separate threads. One is that we can now use data and AI to build all kinds of expert systems. AI will go into every field, every application, every sector. Humans are very good at this; we cannot run fast so we invented cars, we cannot fly so we invented planes. In this regard, cars and airplanes are expert systems. So we build more expert systems to help us to make a more efficient, better society. This will be huge; this is why people are so excited about AI. That’s the practical outcome.

The other side is the scientific thread, namely, understanding what human intelligence is and building AI systems rivalling human intelligence. When I was in elementary school, I always adored people who could do quick calculations without a pen and paper, or a calculator. We used to think that such people are very intelligent. But let me ask you, would anyone think that such skills are what it means to be intelligent today? Of course, no one can beat computers in computation. So the development of AI and computers has helped us to understand our [human] status.

I’m very excited about the future of deep neural networks where biologists, neurologists, doctors and AI experts work together to understand and simulate the brain. Right now there are already some hints that such interdisciplinary research could help people who suffer from memory loss or a brain function deficiency. I actually see computers or AI as an extension of human intelligence, helping us achieve more.

One way that AI has changed businesses is through chatbots, which serve as virtual assistants for many activities. Could you tell us more about Xiaoice, a chatbot that was developed at Microsoft Research Asia?

HHW: Xiaoice [微软小冰 in Mandarin, or ‘Microsoft Little Ice’] started as an incubation project because we didn’t really know how it would fare. It has now been a little more than two years and we are very happy with the results. We launched its Japanese version Rinna in Japan about a year ago. The number of users in China and Japan has long exceeded 40 million.

The most important parameter is engagement, which we measure with something called conversations per sessions, or the number of round trip dialogues conducted with Xiaoice. Right now, the average number is more than 20. This is very amazing because if you think about it, the number of conversations per session you have with your friends and family on a messaging platform like Skype, WhatsApp or WeChat is probably two or three; no more than five.

Everyone knows that Xiaoice is a chatbot, not a real human being, and yet they are willing to chat with Xiaoice for 20 turns. People’s time is so valuable; I don’t think they would do that if Xiaoice were not saying something interesting.

Since the dawn of AI, chatbots have been heavily studied. However, older chatbots like ELIZA failed because they only stayed in the lab and were never deployed to real users. For Xiaoice, we took a data-driven approach and mined real human conversations on social networks. Most importantly, once deployed we had real data— people chatting with Xiaoice. This data in turn helps us to understand what users want so that we can continue to improve the product.

What are some of the key lessons you have learnt from developing Xiaoice?

HHW: One of the things we learnt was that even though people are very active on social networks, the more they used social networks, the more lonely they sometimes felt. People need some sort of emotional connection, which is why they use social networks in the first place. But there are really two types of social network connections: One is with your very close friends and family, and Xiaoice is not trying to solve that.

The other type of connection is where you discuss stuff with people you don’t know personally, but maybe share some similar interests. Let’s say you post something on your blog discussing a particular topic. Typically, your post will get no reply and you probably feel that you have been ignored because nobody posts anything related to your post. When we built Xiaoice, a lot of people sent Xiaoice thank you notes saying that now every single one of their posts gets a reply, so they feel cared for, that their opinions matter.

Xiaoice has done lots of interesting things, including hosting a weather report on TV. How else do you see Xiaoice being used?

HHW: Xiaoice has a simple interface and can get users chatting with natural language interaction on multiple platforms. For example, if you go to the official WeChat account of the Dunhuang caves, a cultural heritage site along the Silk Road, you can chat with the account which is integrated with Xiaoice, and get information about the different paintings in the caves and so on, without the Dunhuang site doing any extra work. Xiaoice has already been integrated with many official accounts on WeChat and e-commerce platform JD.com.

The other thing that Xiaoice can do is go beyond chatting in text; we can also deal with image and video. We sometimes chat in emoticons, but many times we also chat in pictures, taking photos to share with our friends. That’s also how we chat on social networks. Xiaoice can also comment on what is in the picture or video, and at the same time, when appropriate, also reply with some picture or emoticon. The chat experience is more than just text. With a smartphone, we can have all this multimedia and multimodality built in.

What other interesting developments can we expect from Microsoft Research Asia in the next few years?

HHW: In 2016, we announced something called the Microsoft Bot Framework, which helps third parties to build natural language bots to engage with their customers. These bots can take the place of phone-based customer support, and have the advantage of being available any time. When the bot doesn’t have the answer to your questions, it can seamlessly transition to a human operator. We are actively working with a government agency to use such bots to serve the citizens by answering questions about different government services.

Another thing we want to do is to democratize AI. The reason AI is hot now is because we are really reaching a stage where it can serve society at large. It’s very important for us to make AI more accessible to all companies and people. At Microsoft we build all this AI technology in the Cloud and make simple APIs so that every developer can use them. Apart from the bots, we have Cognitive Services that offer APIs on vision, on speech, on natural language, knowledge and search.

At Microsoft we know software and technology, having done AI for at least 25 years, but we are not experts in health, or manufacturing, or transportation. If we can make AI more accessible, each government, company or individual need not invest in the core technology but can focus on their own area of expertise and use AI as a tool to solve their own problems. I think that will be a very great opportunity.

This article was first published in the print version of Asian Scientist Magazine, January 2017. Click here to subscribe to Asian Scientist Magazine in print.

———

Copyright: Asian Scientist Magazine.

Disclaimer: This article does not necessarily reflect the views of AsianScientist or its staff.