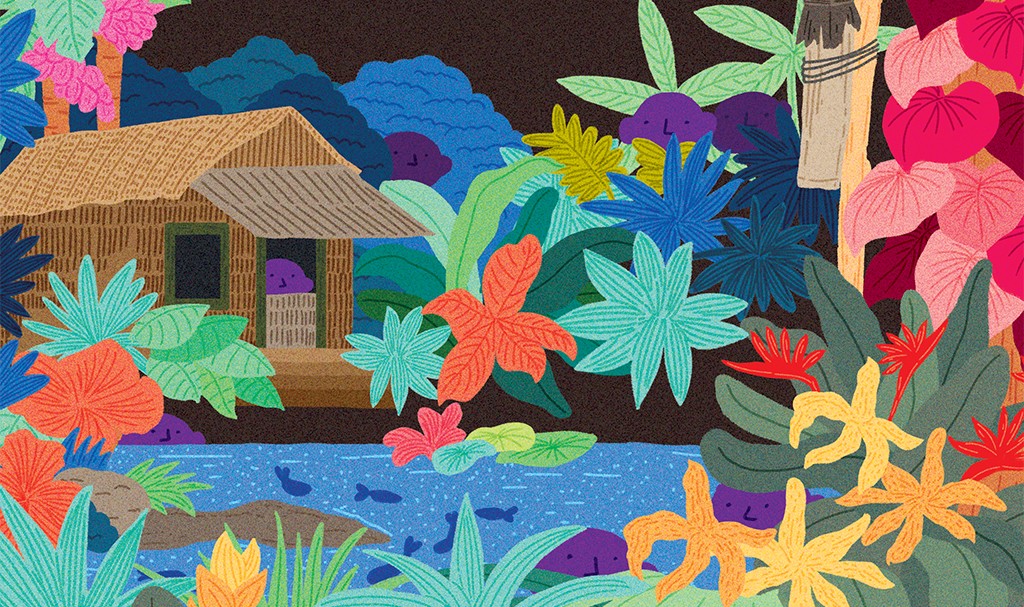

AsianScientist (Nov. 17, 2025) – Just when India was emerging from the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021, Geetha Ramaswami, team lead at SeasonWatch, a citizen science project in India, and two aspiring young ecologists started probing social media for images of flowers. Not for the aesthetic beauty of golden shower tree, the flame of the forest, or the red silk cotton, but to understand how these trees are affected by climate change. Their recent paper in the Journal of Biosciences hints at a geographical pattern of these three flowering plants in India.

In 2010, Ramaswami founded SeasonWatch.in, a platform for citizen scientists to register a tree in their neighbourhood. Then, each week, the citizen scientists observe the quantity of leaves, flowers, and fruit on the tree. This way, scientists with access to the data could figure out seasonal patterns of leafing, flowering, and fruiting in the trees.

“The first data were actually contributed by school children and teachers from the state of Kerala,” said Ramaswami, referring to an eco-club program called SEED (Student Empowerment for Environmental Development). “And 15 years later, that is still the most active and contributive group of citizens.”

In 2021, Ramaswami noticed that many people uploaded photographs of flowers on social media, and sometimes it was possible to extract metadata — including the date and location of the photograph — from the images. That’s when she realised they could combine the power of social media with SeasonWatch data to determine the flowering plants’ seasonalities.

Since social media users posted images of these plants from across India, they could also study whether the same flowering plants bloom at the same time everywhere. In the Global North, studies have shown that trees respond to changing environments by shifting the timing of leaf-out, flowering, and fruiting over the long term. “We need large-scale long-term studies in the tropics to understand what trees do here,” explained Ramaswami.

The team of three annotated by hand between 250 and 350 images from social media posts on Facebook, Instagram, and X (formerly Twitter), image-based citizen science portals like the Indian Biodiversity Portal and iNaturalist, and digital photo repositories like Flickr.

Sometimes, the same trees have different strategies for survival in different climates. For example, the commonly observed Amaltas tree, with its distinctly bright yellow flowers, has different survival strategies in dry and wet regions. In dry areas, they first shed all their leaves before flowering, but in regions receiving sufficient rain, they don’t shed their leaves even in the dry season. So, to determine whether the trees are responding to a changing climate, scientists first need to understand how trees in the same areas behave over time.

The group studied the ‘golden shower tree’ (commonly known as Amaltas), the ‘flame of the forest’ (commonly called Palash), and red silk cotton (widely known as Semal). Their analysis of 3.5 years of collective data showed that the datasets from social media and SeasonWatch complemented each other.

“More or less both of these data sets, which are collected in a completely different format, with completely different reasons, are still conveying the same information,” said Ramaswami. Similar studies in temperate climates have yielded conflicting results from citizen science and scientifically collected datasets.

When the team plotted the flowering patterns of Amaltas, Palash, and Semal, all three trees showed signs of flowering throughout the year. Amaltas showed signs of flowering throughout the year, even at the same latitudes, especially up to 13°N, which passes close to Bengaluru in the state of Karnataka. It is especially noticeable in Amaltas in the southern Indian state of Kerala, where it used to flower only in March and April. “But now people are seeing trees with flowers even in September, October, November,” said Ramaswami, which could be an indication of a changing climate.

At northern latitudes, the datasets were limited to draw concrete conclusions about the trees’ seasonality, though they suggested that the same trees bloomed over limited periods. That points to geographical differences of the same plants at different latitudes.

Ramaswami admitted that scientists need more public participation through the Season Watch project to draw concrete conclusions about the impact of climate change on flowering patterns of these trees. While temperature and humidity could affect the flowering, the presently analysed data could not conclusively establish that. Language barriers, smartphone access, etc., could also create differences in citizen science data collection across India. For social media posts, sometimes photographs lack the metadata that scientists need, like the time and location of the photograph, thus rendering them unusable for scientific purposes.

Still, the project establishes the feasibility of using data collected by citizen scientists and from social media to address scientific questions. Ramaswami is also working with her colleagues at the Nature Conservation Foundation, a charity organisation, SeasonsWatch is a part of, and elsewhere to establish similar patterns of tropical trees, such as jackfruit, mango, and tamarind.

—

Source: Seasonwatch: Images: Shutterstock/RobinsonThomas

The study can be found at: Latitudinal patterns of flowering phenology of three widespread tropical species from public media and data repositories