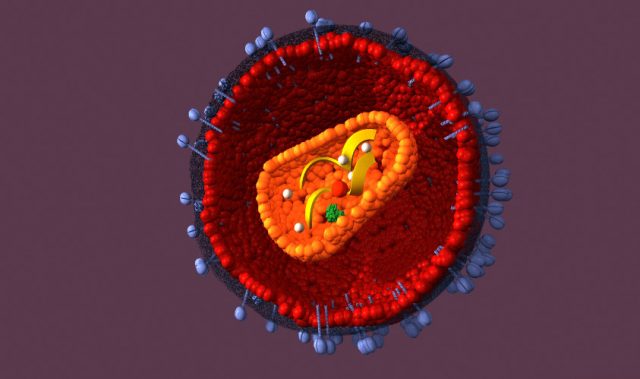

AsianScientist (Feb. 27, 2012) – Lack of access to anti-retroviral therapy (ARV) to treat HIV has left thousands of patients in Myanmar with deteriorating immunity and increased vulnerability to tuberculosis (TB), say health workers.

“The situation is dire,” said Peter Paul de Groote, head of Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in Myanmar. “The gap between the treatment that is needed and what is received is unacceptably high.”

ARV providers in Myanmar – of whom MSF is the largest – are concentrated in Yangon and Mandalay divisions, and Shan and Kachin states, which account for more than 60 percent of the country’s 133 ART distribution sites, according to UNAIDS Myanmar.

“The unfortunate case is that many people have to travel far to access treatment. This country has the potential to treat more people, save more lives and prevent transmission by expanding service provision,” Sung Gang, the UNAIDS Myanmar country coordinator, told IRIN from Yangon.

But according to MSF, funding is the biggest problem. When donors did not deliver on pledges, the Global Fund to Fight HIV, Tuberculosis and Malaria cancelled its Round 11 funding in late November.

While a Transitional Funding Mechanism has been established to provide emergency relief to current recipients, which will run out of money before 2014, it only covers essential services such as HIV treatment, care and prevention, leaving ARV providers unable to expand to other needed areas, notes MSF.

Scale-up interrupted

Funds from Round 11 were expected to treat 46,500 more patients in Myanmar, according to a recent MSF study.

Of the estimated 240,000 HIV-positive people, only 24 percent receive ARV therapy. Roughly 85,000 people need treatment but cannot access it, causing up to 20,000 preventable AIDS-related deaths annually, according to MSF.

“The Ministry of Health, MSF, and the hospitals all have the willingness and capacity to scale up. There are a lot of new donor pledges (going into Myanmar) but not for HIV,” MSF’s De Groote said.

Doctors are forced to prioritize treatment for patients in the most advanced stages of HIV/AIDS, despite proof that earlier treatment decreases transmission rates and improves health outcomes, according to the Inter-Agency Standing Committee’s (IASC) 2010 Guidelines for addressing HIV in humanitarian settings.

“Turning back patients is a difficult and impossible choice. We have to tell them, come back when you get sicker,” said Khin Nyein Chan, MSF’s deputy medical coordinator in Myanmar and a doctor at the NGO’s clinic in Yangon, one of four nationwide.

While the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends starting ARV medications when an HIV patient’s CD4 count, a specialized immune system cell measure, has dropped below 350 cells/mm3, doctors in Myanmar administer ARVs only to those with CD4 levels below 150 cells/mm3.

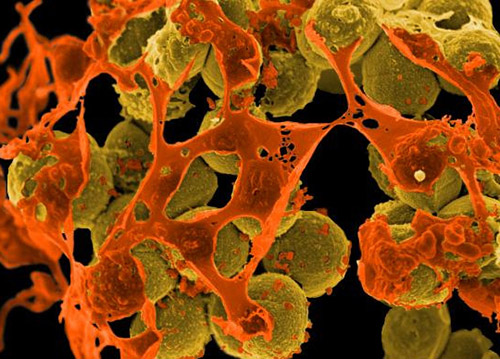

“They have to wait until severe life-threatening and opportunistic infections are in their bodies before we can treat them,” said Khin Nyein Chan.

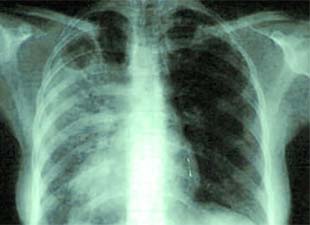

TB threat

TB is one such opportunistic infection. An HIV-positive status can increase the chance of contracting TB by up to 37-fold, according to WHO.

In Myanmar, 300,000 people are infected with TB – 60,000 of whom are also HIV-positive – according to MSF.

The increased incidence of airborne TB among HIV patients not taking ARVs raises the likelihood that it will spread among the general population, said Maria Guavara, MSF’s medical coordinator. “HIV/AIDS and TB are a lethal combination. Treatment of HIV drops the instance rate of TB,” Guavara said.

At Phoenix Association, a Yangon-based social support centre for HIV-positive people, patients seek solace from debt and disease.

One patient from Phyuu Township of Bago Division in the country’s south, Sai Hlaw Aung, 33, told IRIN in 2011 that battling HIV and TB had made him too weak to continue working as a bamboo cutter.

“Now I am not as strong as before. I have no idea how I could earn household income when I go back home,” said Sai Hlaw Aung.

The association allows out-of-town patients to sleep in the office while undergoing treatment in Yangon. Space is tight.

“Currently we need shelter to accommodate the people,” said Thiha Kyaing, head of the association told IRIN. Little has changed since.

“We don’t just want to bridge the treatment gap and walk away. We need sustainable programmes, and the sooner the better,” De Groote said. “If we don’t treat people now we will lose them,” he added.

——

Source: IRIN; Photo: Jo Kuper/MSF.

Disclaimer: This article does not necessarily reflect the views of AsianScientist or its staff.