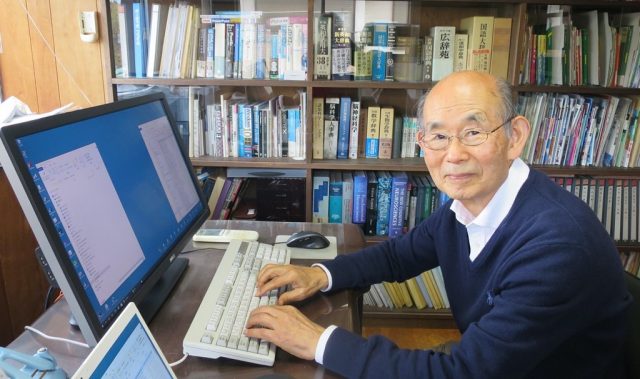

Shoko Takahashi

CEO

Genequest

Japan

AsianScientist (Jan. 11, 2019) – When it comes to having a deep understanding of health and disease, Dr. Shoko Takahashi thinks the devil is in the DNA. Even as a graduate student at the University of Tokyo, Japan, she was already toying with the idea of genomics-driven medicine. Noticing that most databases consisted of genomic sequences obtained from Western individuals, she was determined to create a repository of Asian genomes—one that she believed would benefit clinicians, researchers and, ultimately, patients in the region.

To achieve her goal, Takahashi founded Genequest in 2013 despite not having any background in business or entrepreneurship. She was still a student then, but she credits her relative inexperience for her ability to think outside the box. Today, Genequest provides personal genome testing and analysis services, mostly in Japan, and the data generated is going towards the genome database she originally set out to establish.

Takahashi shared with Asian Scientist Magazine her goals and gave advice on how scientists can maximize their potential beyond the lab.

- How would you summarize your research in a tweet?

I’m establishing a large human genome database, accumulated through personal genome testing, for medical and scientific research institutions.

- Describe a completed research project that you are most proud of.

I’m proud of how we are providing personal genome analysis services for individuals mainly in Japan. These efforts are aligned with our intention to help clinicians and scientists draw insights from genomic data.

We now have more than 20 collaborative research projects that rely on our human genome database. The various topics we’re studying include depression, illnesses associated with dietary patterns or lifestyle, as well as conditions caused by stress.

- What do you hope to accomplish with your research in the next decade?

By mapping genomes, I hope to understand the fundamental mechanisms of biology and life, which will contribute to the development of solutions that enhance health and personal well-being. I want to continue to grow the field of genome-driven innovation.

- Who (or what) motivated you to go into your field of study?

There are many doctors in my family, so I had to decide whether to follow in their footsteps or not. But I felt a calling to go beyond just treating patients in clinics and hospitals, and I wanted to adopt a broader perspective on science. Thus, I chose to become a researcher in the field of life science instead.

- What is the biggest adversity that you experienced in your research?

It was initially difficult to find mentors at the forefront of genomics research who could help accelerate our research. I tried to meet many researchers at scientific meetings and symposiums, and eventually managed to build a network and gain sufficient support from some researchers.

- What are the biggest challenges facing the academic research community today, and how can we fix them?

In Japan, we do not have enough vacancies in academia for researchers. As a result, many highly-qualified individuals, some of whom have PhDs, end up in positions that do not maximize their ability. I think this is not only an economic loss for Japan, but for the world as well.

To overcome this problem, researchers firstly have to accept the reality that research ability and educational background no longer guarantee a career in science. They should also realize that there exists more diverse job opportunities for researchers beyond academia, and actively seek out these opportunities.

- If you had not become a scientist, what would you have done instead?

I think being a scientist really suits me. I’ve never given much thought to pursuing an alternative career.

- Outside of work, what do you do to relax?

Exercise helps me relax, so I visit the gym several times a week.

- If you had the power and resources to eradicate any world problem using your research, which one would you solve?

I want to solve problems in healthcare and, if possible, eliminate all diseases from the world.

- What advice would you give to aspiring researchers in Asia?

I am confident that careers for researchers will be diversified by changing job market requirements. The strong emphasis on innovation in Asia will also open up a new dimension for scientists and create new roles for them.

For instance, my core function now is to be the CEO of my company, but my research expertise has been indispensable in setting the future direction of the business. Hence, I encourage aspiring scientists to think about their careers from a broader perspective; to take a bird’s-eye view of academia and industry and break out of conventional roles defined by their seniors or predecessors.

This article is from a monthly series called Asia’s Rising Scientists. Click here to read other articles in the series.

———

Copyright: Asian Scientist Magazine; Photos: Shoko Takahashi.

Disclaimer: This article does not necessarily reflect the views of AsianScientist or its staff.