AsianScientist (Nov. 2, 2016) – Looking for ‘snapped’ spindles could be a faster and easier way to discover new drugs, according to research published in Genes to Cells.

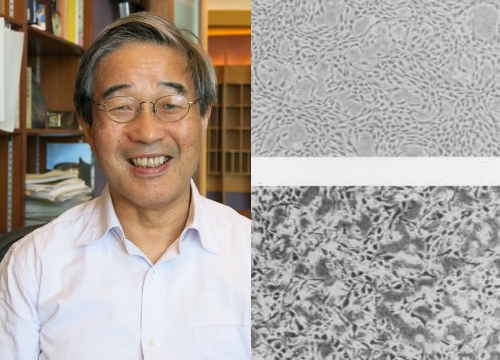

The study, led by Dr. Norihiko Nakazawa in the G0 Cell Unit at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University, centered on the use of a specific anti-cancer drug, ICRF-193, which targets a protein called DNA topoisomerase II. As part of his research, Nakazawa treated fission yeast with ICRF-193 and observed the effects.

Malignant, or cancerous, cells exhibit a much higher rate of replication and proliferation than normal ones. The rapid growth of these cells can result in tumor formation and metastasis, or the spreading of cancer to other parts of the body. Fortunately, scientists have been able to exploit these properties to create new treatments.

Since the proteins involved in DNA replication are considerably more active in cancer cells than in normal ones, researchers have discovered that drugs which target these proteins will disproportionately affect the malignant cells. These drugs are designed to only affect active proteins, so that even though the same proteins exist in normal cells, the majority of the normal cells will contain inactive proteins at the time of treatment, and thus be unaffected.

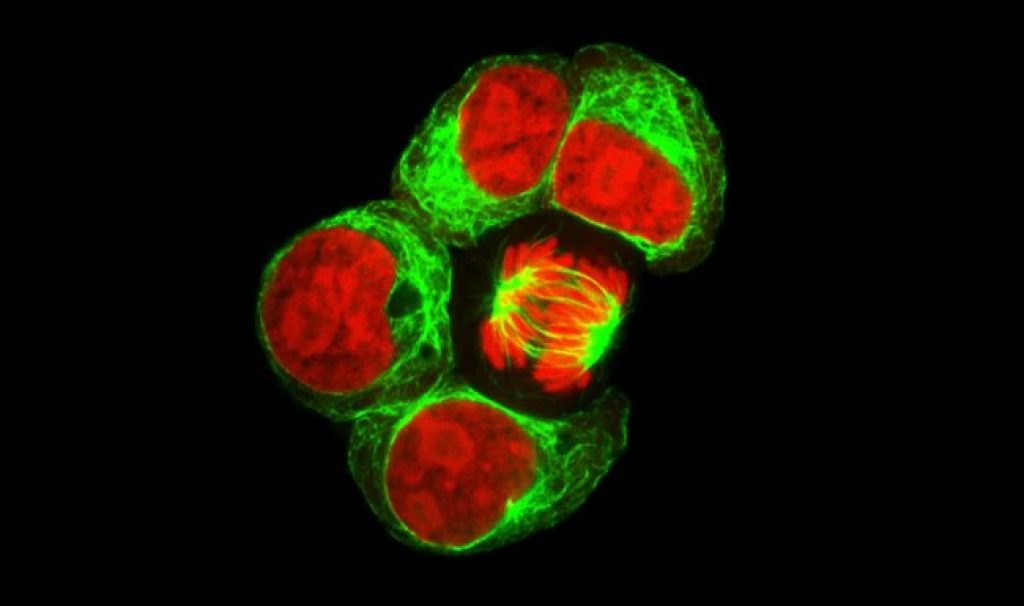

Typically, during cell reproduction, DNA is copied so that a cell temporarily contains twice the amount of DNA than it normally does. These two copies of chromosomal DNA are pulled to different ends of the cell by a protein structure called the mitotic spindle. Once the chromosomal DNA is separated, the cell begins to divide into two identical daughter cells.

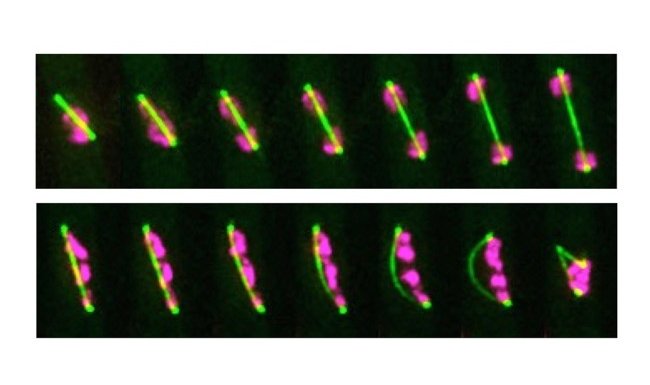

Bottom: ICRF-193 treated cells, which are unable to separate normally. The chromosomes can partially separate, as seen in the far left, but as the spindle elongates, it is unable to further separate the chromosomes, eventually bending and snapping, as seen in the far right of the figure.

Credit: OIST.

When Nakazawa treated fission yeast with ICRF-193, he noticed that the cells appeared to have difficulty separating after DNA replication had occurred. Instead of separating normally, the mitotic spindle appeared to continue to lengthen despite failing to fully separate the two copies of DNA, producing an arched shape until eventually snapping in the middle. This ‘arched and snapped’ appearance seemed to be unique to the ICRF-193 treated cells.

According to Nakazawa, fission yeast is a low cost, relatively fast growing and easy to use model system, making it advantageous for use in drug screens. Time and cost are often major hurdles in the process of drug development, so any discoveries that expedite the process can help get the next cancer cure in the hands of patients sooner, he added.

The article can be found at: Nakazawa et al. (2016) CRF-193, an Anticancer Topoisomerase II Inhibitor, Induces Arched Telophase Spindles That Snap, Leading to a Ploidy Increase in Fission Yeast.

———

Source: Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University.

Disclaimer: This article does not necessarily reflect the views of AsianScientist or its staff.