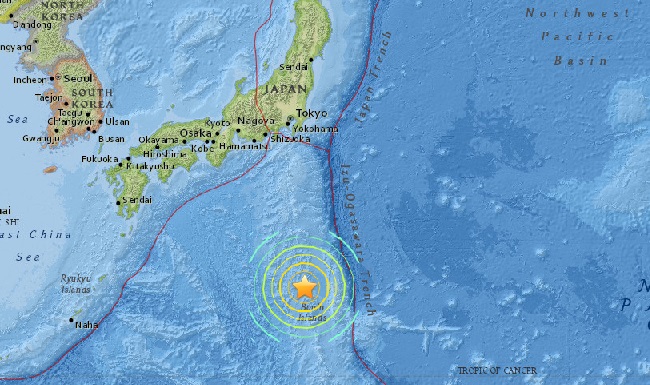

AsianScientist (Dec. 7, 2011) – NASA researchers have discovered that the destructive tsunami generated by the March 2011 Tōhoku-Oki earthquake was a long-hypothesized “merging tsunami” that doubled in intensity over rugged ocean ridges, amplifying its destructive power before reaching shore.

Satellites captured not just one wave front that day, but at least two, which merged to form a single double-high wave far out at sea – one capable of traveling long distances without losing its power. Ocean ridges and undersea mountain chains pushed the waves together, but only along certain directions from the tsunami’s origin.

“It was a one-in-ten-million chance that we were able to observe this double wave with satellites,” said Dr. Y. Tony Song, the study’s principal investigator from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), at the American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco.

“Researchers have suspected for decades that such ‘merging tsunamis’ might have been responsible for the 1960 Chilean tsunami that killed many in Japan and Hawaii, but nobody had definitively observed a merging tsunami until now,” he said.

Calling it akin to “looking for a ghost,” Dr. Song said that a NASA/French Space Agency satellite altimeter happened to be in the right place at the right time to capture the double wave and verify its existence.

Prof. C.K. Shum, a collaborator from Ohio State University, remarked on the team’s luck – not only in the timing of the satellite – but also to have access to such detailed GPS-observed ground motion data from Japan to initiate Dr. Song’s tsunami model, and to validate the model results using the satellite data.

The NASA/Center National d’Etudes Spaciales Jason-1 satellite passed over the tsunami on March 11, as did two other satellites: the NASA/European Jason-2 and the European Space Agency’s EnviSAT. All three carry a radar altimeter, which measures sea level changes to an accuracy of a few centimeters.

Each satellite crossed the tsunami at a different location. Jason-2 and EnviSAT measured wave heights of 20 cm (8 inches) and 30 cm (12 inches), respectively. But as Jason-1 passed over the undersea Mid-Pacific Mountains to the east, it captured a wave front measuring 70 cm (28 inches).

The researchers conjectured ridges and undersea mountain chains on the ocean floor deflected parts of the initial tsunami wave away from each other to form independent jets shooting off in different directions, each with its own wave front. Previously, these maps only considered topography near a particular shoreline.

Song and his team were able to verify the satellite data through model simulations based on independent data, including the GPS data from Japan and buoy data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunamis (DART) program.

“Now we can use what we learned to make better forecasts of tsunami danger in specific coastal regions anywhere in the world, depending on the location and the mechanism of an undersea quake,” said Prof. Shum.

——

Source: Ohio State University.

Disclaimer: This article does not necessarily reflect the views of AsianScientist or its staff.